by Barry Creamer

There are a few icons in American life that are so pervasive that we cannot ignore them. Not only can we not ignore them, but we so idolize them that we have a hard time separating the icon from the person. Billy Graham is one of those figures.

There are a few icons in American life that are so pervasive that we cannot ignore them. Not only can we not ignore them, but we so idolize them that we have a hard time separating the icon from the person. Billy Graham is one of those figures.

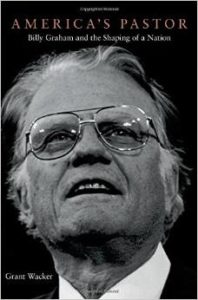

I sat down recently with Duke University professor Grant Wacker to talk about his new book, America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation, which discusses Graham’s monumental influence on American culture during the turn of the 20th century.

Barry Creamer: What provoked you to write this book?

Grant Wacker: There are many books written about Billy Graham, but I thought that a book examining his relationship with American culture and history was missing. So my book looks at the intersection between Graham and the larger trends of American life.

Creamer: People all over the world would probably say that Billy Graham is one of the most influential people of the last hundred years. Where does he fit in the history of Christianity in America?

Wacker: I argue in the book that he ranks with Martin Luther King, Jr. and Pope John Paul II as three of the most influential Christians of the 20th century, particularly the second half of the century. Though they were very different people, their influence far beyond the church was overwhelming.

What piqued my interest for this project is how Graham brought the church and the secular worlds together. I would argue that he was the most important preacher of the century, but at the same time, he was the friend of ten presidents and had strong views against Communism but later for nuclear disarmament. He had the public visibility that preachers rarely, if ever, have.

Creamer: You’ve talked about the ‘early’ and ‘late’ Billy Graham. Where would you draw that dividing line?

Wacker: Probably the early 1970s. In the 1950s and through the 1960s, he would be most commonly associated with strong anti-Communism and as an early supporter of the Vietnam War. That changed in the 1970s as he matured and traveled. He became far more irenic, much more aware of the complications of America and the world.

Throughout his life, he was never only a preacher. He was always involved in public affairs. From the beginning of his ministry, he was involved with Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, and other presidents. That never changed. But toward the middle of his career, he gained more appreciation for the needs and problems of the rest of the world. He became progressive on civil rights and drew attention to world hunger and disease. He was also careful not to associate himself with the Christian Right. He stayed out of the culture wars.

He was once asked about his changing perspective, and he had a very simple answer: “I have seen some things.” He had preached in nearly a hundred countries to over 200 million people (not counting billions via electronic media), receiving over three million decision cards. He had enormous exposure that didn’t just impact the world, but impacted him.

Creamer: What about his celebrity? Where would you place the shift from well-known figure to iconic figure?

Wacker: The iconic status began early. By the early 1950s, when he was still in his 30s, he was the most prominent evangelist in America. A poll taken in the 1950s showed that the majority of Americans already recognized his name and felt positively toward him. By his great New York crusade in the mid-1950s, there was no rival. It was Billy Graham and everyone else. And what’s fascinating is that he never sought it; it came to him.

Creamer: If evangelicals had saints, he would be one.

Wacker: He would be the top saint! He received millions and millions of letters from people all over the world. People confessed their sins and shared their fears and their grief with him. Many of them simply expressed gratitude toward him. He couldn’t reply to every one of them because they came in semi-trucks, but he knew about them. And though he only read a small portion of them, every letter received a reply from his staff.

He in many ways actually played the role of pastor-confessor. You get a sense from these letters that he wasn’t just a saint-like figure, but their pastor.

Creamer: Hence the name of the book, America’s Pastor.

Wacker: Exactly. And it’s interesting that we’ve been using the word ‘icon,’ because the second chapter of the book is titled “Icon.” The key point is that the press elevated Graham rather than him elevating himself. The press saw a figure that they wanted to highlight because he sold papers. He liked reporters and reporters liked him. He became a brand.

He had everything the media wanted. The media regularly commented on his Hollywood-handsome looks. His Southern accent was very important because the South was becoming increasingly popular in American culture—the “southernization” of American life. Of course, he was also a terrific communicator.

He also put pieced together a huge media empire. He utilized radio, television, magazines, books, you name it. He was very good at using media to keep his message front and center. And like we said earlier, he was also not shy about making relationships with presidents.

Creamer: Were you able to have any direct interaction with Graham during this project?

Wacker: Yes, and that was my favorite part of the project. After I was well into the project, my wife and I had the great privilege of visiting with him four times. He was well into his late 80s and early 90s, so his public ministry was mostly behind him, but one could not sit in his presence without feeling his charisma.

When sitting with him, one also senses his extraordinary humility. There’s a sense in which Billy Graham has no idea that he’s Billy Graham. Though he does understand his influence, he is a man of stunning humility. For example, on one occasion he asked my wife and me, “What brings you to the area?” And I think it was absolutely genuine. He didn’t have the sense of how much people really wanted to meet him.

Creamer: What audience are you trying to target with this book?

Wacker: I quip with my students that it’s not for historians; it’s for the Barnes & Noble browser—the interested, thoughtful, non-specialist. It’s especially written for Christians who are interested in one of the most influential Christians of the turn of the century.

Barry Creamer is President and Professor of Humanities at Criswell College and a trustee and research fellow at the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. Follow him on Twitter.

Barry Creamer is President and Professor of Humanities at Criswell College and a trustee and research fellow at the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission. Follow him on Twitter.

—